Introduction

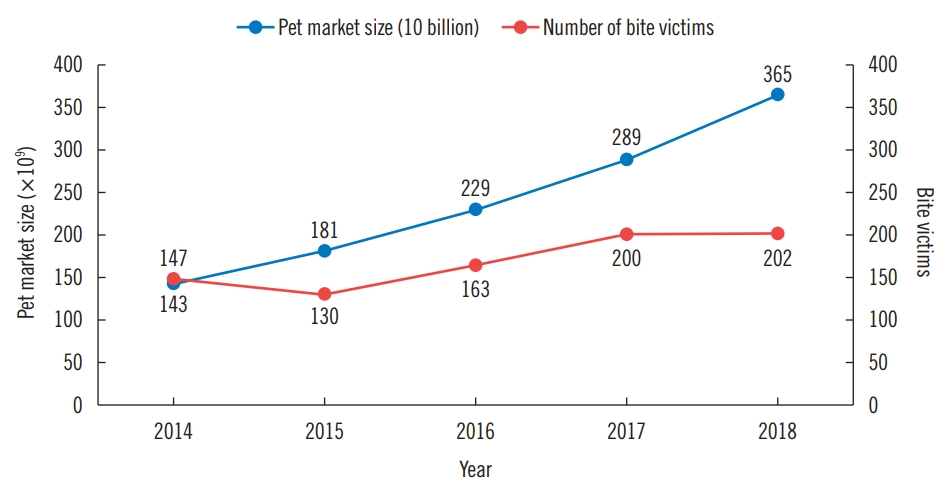

Korean household pets include over 10 million dogs and cats, demonstrating a steady increase [1]. Animal bites and related injuries are also on the rise; according to the medical records from our institution, the number of visits owing to animal bites has risen each year over the past decade. As the incidence of animal bites has grown to epidemic proportions, animal bites are increasingly being recognized as a significant health care problem (Fig. 1) [2,3]. Although there have been some studies on animal bites in Korea [3-6], there has been no statistical analysis of the large number of animal bites observed along with the recent increase in pet population.

Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment is required for many of the dog and cat bites, because these injuries can require surgical intervention or hospitalization, and may even result in permanent functional impairment (Fig. 2) [5,7-10]. Animal bites and the associated injuries can create medical problems in the community, loss of work, and increased medical expenses [11]. Therefore, health providers and the public in general need a better understanding of animal bites, related potential risks and proper management of bite injuries.

We investigated the epidemiologic aspects of animal bites using the medical records collected at our medical center over the last 5 years. Our study aimed to find differences between dog and cat bites and several factors that may affect the bite incidence, hospitalization, and the need for surgical intervention.

Methods

Ethics statement

This retrospective study was approved by Ethics Review Board of Gwangmyeong Sungae General Hospital (approval No. KIRB-2019-N-004), and patients who underwent the procedures provided informed consent before the study took place. The patients gave written informed consent for the use and publication of their images. From January 2014 to December 2018, we studied 942 patients who were treated at our institute for animal bite injuries.

Inclusion criteria

All patients who presented to our institute with a chief complaint of dog or cat bites were included.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who came with bite abrasions only involving the epidermal layer, those who failed to follow-up before complete healing of the wound, and those with bites that were not from dogs or cats were excluded. This ruled out 119 patients from the 942, leaving 823 in our study.

Data analysis

Patient demographics, medical histories, physical examination findings, bacterial wound culture results, course of hospital treatment including surgical intervention or hospitalization, duration of treatment, and long-term follow-up data were collected from medical records. We analyzed the incidences of animal bites by various factors, including the sex and age of the patient, type of animal, season, and anatomical site of injury. For age distribution, we looked at seven age groups: 0 to 9 years, 10 to 19 years, 20 to 29 years, 30 to 39 years, 40 to 49 years, 50 to 59 years, and more than 60 years. For seasonal distribution, we split the months of a year into four groups: March through May (spring), June through August (summer), September through November (autumn), and December through February (winter). The anatomical sites of injury were grouped into upper extremities, lower extremities, and face. Data on whether the patient was hospitalized, culture growth from the wound, surgical intervention, and duration of treatment were also collected.

Continuous variables were analyzed using the Student t-test, and categorical variables were analyzed with the chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Logistic regression analysis was used for predictive factors for surgical intervention. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Clinical course

Current guidelines at our hospital prescribed the following management for bite wounds. Every bite wound was irrigated thoroughly with sterile normal saline, and was carefully examined for damaged tendons, arteries, nerves, joints, and bones in the initial evaluation [12,13]. Routine radiologic examinations were performed to rule out bony involvements and residual foreign bodies [14]. Tetanus vaccinations were suggested for dirty wounds or if more than 5 years had elapsed since the patient was immunized [15]. The possibility of rabies was considered for all bite wounds, and emphasis was placed on patient awareness-raising and surveillance of attacking animals [16].

The wounds were left open for delayed closure, or a loose approximation of the skin was made. Devitalized tissue was debrided if necessary under local anesthesia. However, most of the facial injuries were closed primarily for favorable aesthetic outcomes [2,17]. Betadine material was used for dressings. For injuries to the upper extremities, splints were applied for a few days to immobilize the joint and to prevent infection from spreading. The splints were removed within 5 days, after which the patients began moving their joints. Because bite wounds are usually contaminated with pathogens, prophylactic antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanate) were administered early on [10,14,18]. For patients with severe infections, evidenced by purulent discharge or pus, bacterial cultures were performed. Depending on the results of the bacterial culture, in some cases the initially administered antibiotics were replaced with a susceptible antibiotic.

Results

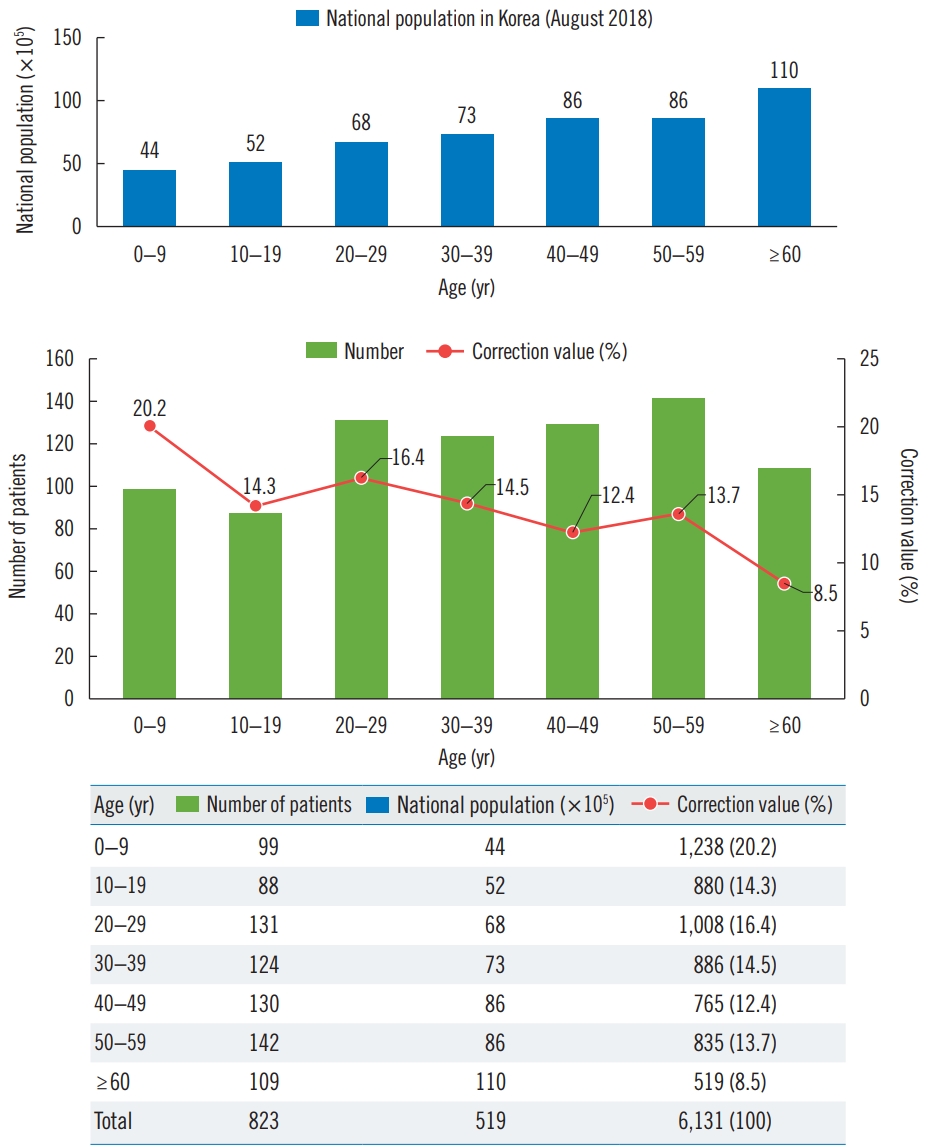

A total of 823 patients from 9 months to 85 years old were evaluated in this study, and the mean patient age was 36.8 years. The numbers of animal bites observed in each age group and the percentages thereof were as follows: 0 to 9 years (n= 99, 12.0%), 10 to 19 years (n=88, 10.7%), 20 to 29 years (n= 131, 15.9%), 30 to 39 years (n=124, 15.1%), 40 to 49 years (n= 130, 15.8%), 50 to 59 years (n=142, 17.3%), and over 60 years (n=109, 13.2%). While incidence of dog bites, and both cat and dog bites together (total bites), were evenly distributed across the age groups, there were more cat bites observed in the younger population (P<0.001) (Table 1).

Males accounted for 46.7% (n=384) of total bite patients, while females accounted for 53.3% (n=439). Of the 384 male patients, 84.9% (n=326) experienced dog bites and 15.1% (n=58) had cat bites, and as for the 439 female patients, 80.4% (n=353) of the bites were from dogs, and 19.6% (n=86) of the bites were from cats. The overwhelming majority of bites were from dogs in both males and females. The proportion of cat bites in women were slightly higher than those in men, but there was no significant difference (P=0.098) (Table 1).

The incidences of dog and cat bites were assessed across the four seasons: spring 24.4% (n=201), summer 26.1% (n=215), autumn 28.9% (n=238), and winter 20.5% (n=169). The occurrences of total bites and dog bites peaked in autumn, whereas cat bites peaked in the summer. However, there were no significant differences in distribution of the bites across seasons (P=0.063); the injuries were randomly distributed throughout the seasons. In addition, while the incidence of total bites increased each year, the ratio of dog bites to cat bites showed no significant changes throughout the different years (Table 1).

Next is the anatomical distribution of dog and cat bites. In the dog bite group, the upper extremities (n=404, 59.5%) were most affected, followed by the lower extremities (n=155, 22.8%) and the lastly the face (n=120, 17.7%). In the cat bite group, the upper extremities (n=121, 84.0%) were the most common site of injury, followed by the face (n=15, 10.4%) and then lower extremities (n=8, 5.6%). Cat bites were significantly more likely to be observed in the upper extremities (P< 0.001) (Table 2).

Of the 823 patients, 91 patients were hospitalized; 78 patients were in the dog bite group, and 13 were bitten by cats. However, for hospitalization rates, there were no significant differences between dog and cat bites (P=0.393).

In the dog bite group, injuries to the upper extremities required treatment for 6.37±6.88 days on average (range, 1–77 days); those to the lower extremities required an average of 4.34±1.91 days (range, 3–17 days); and those to the face an average of 5.82±3.69 days (range, 2–34 days). Altogether, a median of 5.81±5.66 days (range, 1–77 days) of treatment were required for the 679 patients. In the cat bite group, upper extremity injuries required an average treatment of 3.56±2.38 days (range, 3–16 days); injuries to the lower extremities required an average of 2.75±0.71 days (range, 2–13 days), and those to the face required an average of 3.20±1.37 days (range, 2–6 days). All in all, for the 144 patients, a median of 3.48± 2.24 days (range, 2–16 days) of treatment were required. The dog group required significantly longer treatment periods than the cat group regardless of the site of injury (P<0.001) (Table 2).

Bacterial wound cultures were performed when purulent discharge or pus was observed. Among the 144 cat bite victims, bacterial wound cultures were observed in nine patients; no growth (n=5), Pasteurella multocida (n=3), and Neisseria species (n=1). On the other hand, bacterial wound cultures were observed in 72 patients among the 679 dog bite victims, and the results were as follows (Fig. 3): (1) no growth of 65% (n=47); (2) Staphylococcus species of 14% (n=10): Staphylococcus capitis (n=1), S. epidermidis (n=5), S. aureus (n=1), S. hominis (n=1), S. warneri (n=2); (3) Streptococcus species of 7% (n=5): alpha-Streptococcus species (n=4), Streptococcus pneumonia (n=1); (4) Pseudomonas species of 4% (n=3): Pseudomonas stutzeri (n=1), P. aeruginosa (n=2); (5) Micrococcus species of 4% (n=3); and (6) miscellaneous of 6% (n=4): Yersinia (n=1), Escherichia coli (n=1), Neisseria species (n=1), Pasteurella canis (n=1).

There were no significant differences between dog and cat bites in terms of meaningful growth in wound culture results (Table 2).

Of the 823 patients, 84 required surgical intervention (Table 3). Thirty-two patients underwent primary closure, all of whom had facial injuries. However, some cases saw infections, including deep tissue infections that required incision with drainage (n=10), inflammatory swelling and rises in intracompartmental pressure for which fasciotomy was required (n=2), flexor tenosynovitis requiring tenosynovectomy (n=3), and osteomyelitis that called for osteocurettage (n=1). The majority healed with secondary intention, but some did not and required delayed primary closure (n=28) or split-thickness skin grafts (n=2). When nerves or tendons were damaged, the wounds were left open; after confirming that there was no progression of infection, we performed neurorrhaphy (n=2) or tenorrhaphy (n=1). There were three cases of complete digital amputation, all of which were caused by dog bites. Of these amputated cases, immediate replantation (n=2) was attempted when available, and a partial second toe pulp free flap (n=1) was performed for a patient who presented to the emergency department without the distal amputated segment [19]. Between the dog and cat bites, the dog group required more surgical interventions overall (P=0.022), and more so in the upper extremities (P=0.002). However, there were no significant differences between the dog and cat groups in the lower extremities (P=1.000) and face (P=0.753) (Table 2).

In univariate logistic regression analysis, dog bites as opposed to cat bites (P=0.024), face injuries as opposed to those of other regions (P<0.001), and positive culture growth (P= 0.001) seem to be risk factors for surgical intervention. However, in multivariate logistic regression analysis, only face injuries (P<0.001) and positive culture growth (P=0.001) turned out to be significant risk factors for surgery. Age, gender, and season did not seem to affect the need for surgery (Table 4).

Case 1

A 54-year-old woman sustained a dog bite that caused complete amputation of a digit in the mid-level of the middle phalanx of her right index finger. She underwent immediate replantation followed by usual post-replantation care, and special care was taken to prevent infection. The replanted digit survived without severe infection, non-vitalized partial skin was debrided after 3 weeks, and the patient was discharged after 4 weeks, with complete healing of the wound. In her longterm follow-up visit after 14 months, no signs of osteomyelitis were found in the radiologic exams (Fig. 4).

Case 2

A 56-year-old man was bitten by a dog and presented with lacerated wounds, erythema, and swelling in the middle phalanx of his left index finger. Though he was admitted for intravenous antibiotic therapy, the infection worsened the next day, and he subsequently underwent an emergency tenosynovectomy in the operating room. Intraoperatively, the infection was found to have spread over the tendon sheath. After meticulous debridement and copious irrigation, the wound was loosely closed, followed by anti-infectious management. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 24. At his 6-month follow-up, he was found to have almost fully recovered his range of motion (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Household animal bites from dogs and cats in Korea are becoming more common. As most people might get bitten by an animal at least once in their lifetime, animal bites present numerous socioeconomic and health problems. In Korea, Kim et al. [3] conducted a comparative study of dog bites among 103 patients in 2005. In 2013, Lee et al. [5] studied 68 patients who sustained mammalian bites mostly resulting in facial trauma. For osteomyelitis caused by animal bites, there have been two case reports, by Lim et al. [4] in 2016, and by Lee et al. [6] in 2017. As few studies had included large patient populations, we conducted a study that compared bite distributions across various factors in a larger patient population.

Animal bites are traditionally considered a problem for children; most studies have shown that significant proportions of animal bite injuries involve children. Children are at higher risk because of their lack of caution in their interaction with pets, inexperience in handling animals, and their relative inability to defend themselves [8,9,11,20]. In the United States, it was reported that children under 12 years of age account for 50% of all dog bite injuries [13,17]. Kizer [11] reported that 19% of dog bites are observed in children under 10 years of age. In Korea, Lee et al. [5] published in 2013 that 10.3% of patients who sustained bites were under 10 years of age. Similarly, 12.0% of the patients (99/823) from our institution who suffered from animal bites were under 10 years of age. However, taking into account Korea’s low birth rate and current distribution of the nation’s population as of August 2018 [21], we calculated the correction values of incidences for each age group as follows: correction value=number of patients in age group/(general population of age group/total general population).

Still, even after incorporating the distribution of the general population, the incidence was highest (20.2%) in children (Fig. 6).

The high incidence of bite injuries that involved the upper extremities (65%) observed in our study is in agreement with the results of previous studies [3,10,11]. This is probably attributable to people mostly using their upper extremities to provoke animals or protect themselves from attacking animals, and also because the upper limbs provide a better biting surface than other areas. It is believed that as wound healing slows, the risk of infectious complications increases more in the lower extremities than in the upper extremities [22]. However, in our study, the average duration of treatment for patients with lower extremity wounds was shorter than that of patients with upper extremity injuries. We suspect this is mainly because the lower extremity wounds we encountered were less severe, thanks to the protection of clothing and shoes.

In our study, dog bites accounted for most of the bite injuries. Dogs are generally preferred as pets over cats in Korea, reflected in the higher proportion of dog owners, which in turn, corresponds to a potentially greater risk of dog bites. Also, behavioral differences between dogs and cats may affect the bite incidence. While dogs mainly bite to attack or defend, cats primarily use their claws under similar circumstances, resulting in fewer cat bites, but more cat scratches.

We observed a wide variety of wounds, from superficial abrasions to amputation of digits. The three cases of complete digital amputations were all caused by dogs. Dogs have blunt teeth and powerful masseter muscles with strong jaws that can tear soft tissues and result in large open wounds [20]. On the other hand, patients with cat bites usually presented with puncture wounds, which were not as destructive as the wounds associated with dog bites. Some studies have found that the infection rates from cat bites are nearly double that of dog bites. This may be attributed to the sharp and thin teeth of cats that easily penetrate joint capsules or bones and inoculate bacteria into deep closed spaces, resulting in deep tissue infection [10,11,14,20]. However, we can assume that the infection rates of cat bites are lower than those of dog bites because our study found that cat bites are associated with a shorter average treatment period than dog bites.

An apparently superficial, less than severe bite injury may be deeper than it appears and can lead to a severe infection of the joints or the tendon sheath. The superficial vicinity of joints and tendon sheaths in the fingers places them at risk of inoculation by the sharp teeth of animals; animal bites can cause deep lacerations that embed oral and skin organisms into the joint capsules or dorsal tendons [14,20]. Because of the presence of avascular tendons and sheath spaces, injuries in these areas are more susceptible to the spread of infections, leading to high rates of infections and complications [14,23]. For these reasons, we strongly caution against primary closure of bite wounds. Exceptions are made for exposure of deeper structures such as nerves, arteries, tendons, bones, or joints. In these cases, we loosely approximate the skin to prevent desiccation of the deep structures. Once the infection is adequately treated, we then performed delayed wound closure [8,12].

For patients with facial trauma, the wounds were irrigated and cleansed thoroughly, followed by primary closure if necessary. It is well known that bites to the face rarely develop infections, thanks to the abundant blood supply throughout the face [2,17]. We carried out primary closure in 32 patients who sustained bites to the face, and there were no reported cases of infection. Facial bites require precise management because cosmetic disfigurements, such as scars, are more conspicuous on the face, and also because of the chances of developing epidermal inclusion cysts and psychological trauma [5].

This was a retrospective comparative study and therefore has the limitations of a non-randomized, non-case controlled study. In light of the possible bias in this analysis, randomized studies in the future will help validate our conclusions. That said, one of the strengths of this study is the amount of evidence that was collected, as we included far more patients than previous studies that were conducted in Korea. This is also the most recent study to evaluate recent animal bite trends, providing better grounds for prognosis. Furthermore, we analyzed a variety of variables, including the recent increase in number of pets as reported by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs [1] and the distribution of the nation’s population as reported by Statistics Korea [21]. This study thus provides a comprehensive overview of the epidemiology of bite injuries in light of the latest domestic conditions. Future studies that add variables such as the percentage of households with pets by age group and the number of animals raised per household will contribute to a more complete overview with relevant statistics.

All dogs and cats are capable of inflicting bites. In our study, upper extremities were more prone to injury than in other regions. Dog bites required longer treatment periods and more surgical interventions than cat bites. Also, positive culture growth results and facial bite injuries were predictive factors for the need of surgery. Although all bites have the potential to become infected and require surgical intervention, their gravity is often underestimated. Therefore, it is important to raise awareness on the potential impact of animal bites and the need to obtain medical attention as soon as possible. When patients present with bite injuries, early management must be thorough and vigorous, and there should be a low threshold for aggressive treatment [12]. With effective wound management, including local wound care, appropriate antibiotic therapy, and surgical intervention if necessary, animal bite wounds can successfully heal with minimal sequelae.